Culturally Respectful Language When Referring to Native Hawaiian Ancestors, History, Culture and Places

Hawaiian culture is not frozen in time—it is living, evolving, and actively practiced today. Our values, practices, language, and ways of knowing are carried forward through generations, continually shaping how we live, lead, and engage with the world. We honor and carry forward our Hawaiian worldview from Kahiki—the place from which our kūpuna voyaged—to the Hawaiʻi of today, tomorrow, and the future.

Kahiki is more than a physical place; it is a genealogical anchor that directly connects us to our origins within Moananuiākea. It secures the foundation of who we are as Kānaka ʻŌiwi—descendants of wayfinders, warriors, and explorers who first arrived in Hawaiʻi generations ago.

- Mālia Sanders, Executive Director of NaHHA

Word Choice Sensitivities when referring to Native Hawaiians, Hawaiian Culture, Hawaiian History, and Hawaiian Places

In describing Native Hawaiian culture and ancestors, it is important to avoid the term “ancient.” While often used with good intentions, this word can unintentionally suggest that the culture and people it refers to no longer exist—that they belong solely to the distant past.

Referring to our ancestors as “ancient” can create the false impression that their knowledge, traditions, and identity are no longer present—reducing them to relics rather than honoring them as the enduring and living foundation of Native Hawaiian life today.

For similar reasons, we also avoid the phrase “Hawaiians of antiquity.” While it may appear respectful or scholarly, it frames Native Hawaiian ancestors in the same static, disconnected way as the term “ancient.” The term “antiquity” is often used in academic contexts to describe civilizations perceived as no longer living or relevant. This framing does not reflect the ongoing presence, continuity, and deep ancestral lineage of the Native Hawaiian people. Our ancestors are not figures of a bygone era—they are honored as elders whose knowledge systems, values, and practices remain central to Native Hawaiian identity, wellbeing, and worldview today and in the future.

This understanding also aligns with the way we speak about wahi kūpuna, or ancestral places. In a Hawaiian worldview, these are not simply historic “ruins”, “relics” or “remnants” of the past—they are living landscapes, imbued with the continued presence of our ancestors. Wahi kūpuna are places of deep genealogical and spiritual connection, where memory, identity, and practice are still alive. Just as we do not regard our ancestors as extinct, we do not treat their places as abandoned. Both are part of an unbroken, living relationship between past, present, and future.

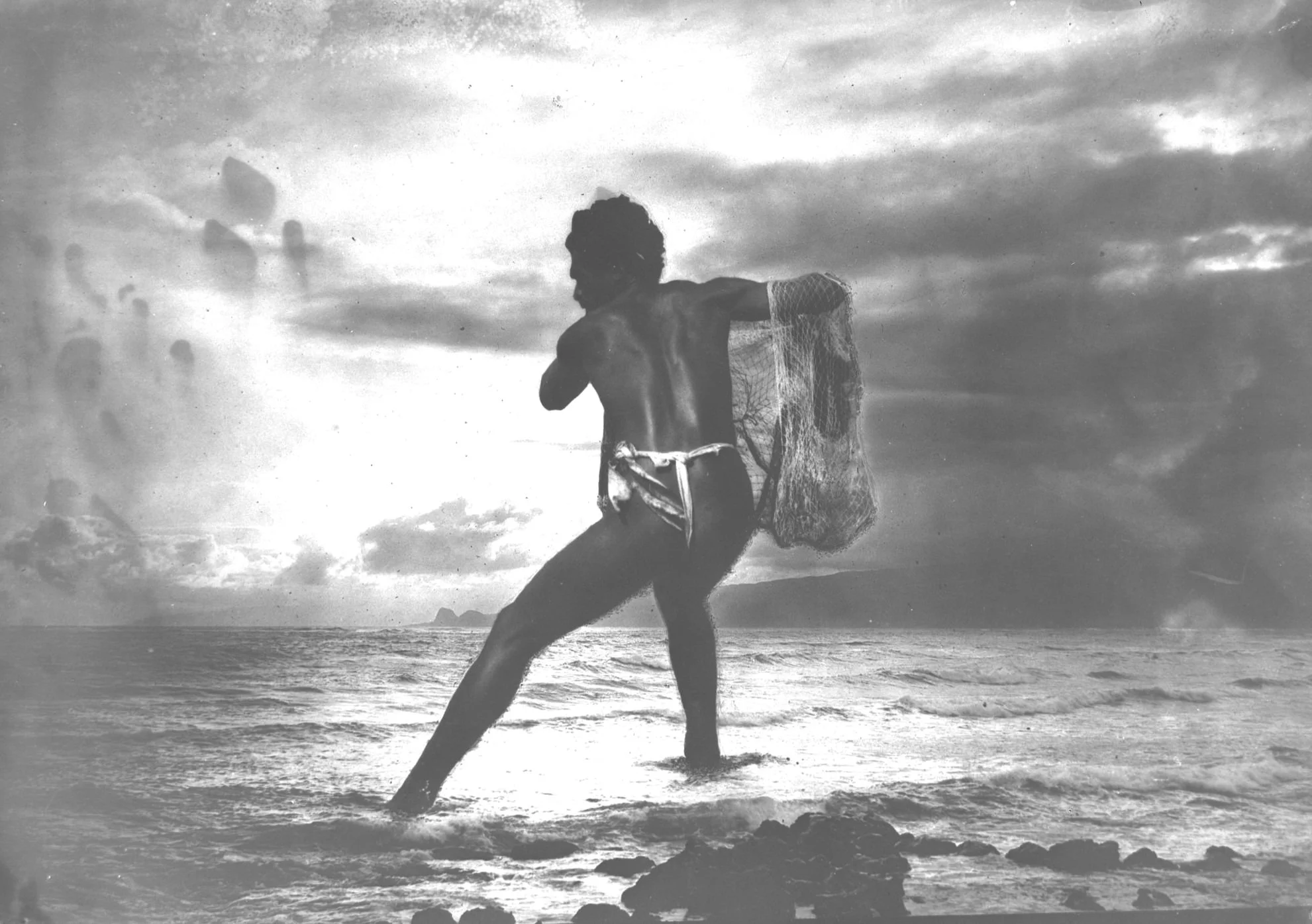

Instead, we encourage the use of terms that more accurately reflect the vibrancy, affirm the continuity and express the endurance of our people and culture, especially when referring to Hawaiians of pre-contact history. Instead, we prefer terms like “kūpuna” (elders) to describe our Native Hawaiian ancestors, early Hawaiian practitioners or early Hawaiian society (to describe specific historical periods). Native Hawaiians see their ancestors and kūpuna as cultural knowledge holders and cultural bearers who they have a direct relationship to since time immemorial.

In the mid-20th century, the term “Hawaiiana” was often used by collectors, educators, and marketers to describe objects, stories, and traditions associated with Hawaiʻi—packaging Hawaiian culture as a commodity, nostalgic or exotic curiosity rather than a living, evolving cultural practice rooted in Native Hawaiian worldview. Today, we avoid using “Hawaiiana” because it tends to generalize or commodify Hawaiian culture, separating it from its ancestral context and ongoing relevance. Instead, terms like Moʻomeheu Hawaiʻi, or Native Hawaiian culture are preferred, as they center Hawaiian identity, sovereignty, and lived experience.

These terms affirm a living connection between past and present—honoring the resilience, adaptability, and enduring strength of the Native Hawaiian people.

We respectfully ask that when writing, speaking, or referring to the time before Western contact and colonization, you do so with cultural sensitivity and awareness. Please avoid language that erases or diminishes the continued existence and relevance of the Native Hawaiian people. Certain terms can carry connotations that conflict with how Native Hawaiians see themselves, and how they understand and honor their history, their kūpuna, their wahi kūpuna, and the living legacy of generations of Native Hawaiian knowledge and practice.